Executive Care

The purpose of this research is to summarize the reason for dispute regarding the length and quality of postpartum coverage provided by Medicaid in Utah and suggest a cost-effective solution. This issue has come to surface due to the fact that in recent years the amount of high risk pregnancies have been increasing in the United States. It has been recommended by numerous organizations and providers, including US government organizations, that postpartum care consist of more than what Medicaid in Utah currently offers.

Introduction and Background

In 2018, it was found that 43% of births in the United States were paid by Medicaid (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2020). In Utah, Medicaid coverage includes prenatal care, labor and delivery, and about 9 weeks of postpartum care (Physician Services, 2021). This postpartum care includes one check-up visit with a healthcare provider such as OBGYN, one evaluation by a mental health professional (12 therapy visits if deemed necessary), and one home visit from a Medicaid nurse (Physician Services, 2021). For mothers with ideal deliveries, traditional postpartum care usually consists of routine follow ups with healthcare and mental health professionals for the first 12-weeks after a delivery (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). In some cases, routine primary care screenings related to pregnancy complications are recommended throughout the rest of the mother’s life (American Diabetes Association, 2021). In addition, because of the increases in pregnancy related mortality rates and risks such as postpartum depression and gestational diabetes many organizations are now encouraging postpartum care beyond the 12-week mark (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023; American Diabetes Association, 2021; Hoyert, 2023; Petersen et al., 2019).

One specific organization that is suggesting this shift to advance postpartum care is The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). In 2016, the ACOG suggested that postpartum care consist of follow up visits within the first 4-6 weeks after birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2016). In 2018, the organization restated their recommendation based upon increasing evidence that postpartum care was most effective when it consisted of routine visits for about 12-weeks after giving birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). The ACOG called this period of recuperation after birth the “fourth trimester” suggesting that it was just as important as prenatal care and created a timeline outlining each stage of the experience (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). The recommendations were also adjusted to clearly state that postpartum care should be individualized for each pregnancy, suggesting that 12-weeks was only a baseline for healthy pregnancies (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). Overall, these changes in guidelines were issued as an effort to protect and inform the healthcare system of the increasing healthcare needs of current postpartum mothers.

1: Increased Postpartum Risk

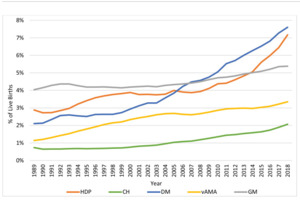

Some organizations and researchers argue that one reason Utah Medicaid needs to adjust their coverage is because the number of mothers with pregnancy complications that can cast their effect for multiple years, such as gestational diabetes and postpartum depression, is increasing. Research performed by Bornstein et al (2020) in “Concerning Trends in Maternal Risk Factors in the United States: 1998-2018” shows trends in the increase of disorders related to pregnancy including chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and advanced maternal age.

Research studies conducted based on billing codes presented by both Alejandro et al (2020) and Hunt & Schuller (2007) suggest that the percentage of pregnancies affected by gestational diabetes have been increasing over the past ten years specifically in the last few years with an estimated jump from 2%-10% of births affected in 2019 to 9%-25% of births affected in 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Research conducted by Layton et al (2021) and DeVoe et al (2020) shows that the number of women experiencing postpartum depression has also been increasing over the past twenty years and has skyrocketed with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic over the last few years. Utah’s suicidal rates are very high, known to be 6th in the nation in 2019 (Utah Department of Health, 2021). This suggests that Utah has a big responsibility to do whatever they can to help residents at risk of depression. The rate of strokes among new mothers linked to prenatal complications is also rising according to the CDC and statistics presented by Chan et al (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021; Chan et al., 2018).

2: Late Postpartum Diagnosis

A second reason that has been supported by multiple scholars is that there are a variety of postpartum complications in which the first symptoms or secondary flare ups are known to take place outside the traditional postpartum follow-up period. For example, postpartum depression is known to be diagnosed for the first time up to a year after delivery (Cantilino et al., 2017). It is recommended by the CDC that women who experienced gestational diabetes get screened for type 2 diabetes not only in the first 6-12 weeks after delivery, but every 1-3 years after giving birth as well (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). It is not uncommon for other postpartum complications to be diagnosed up to two years after giving birth including postpartum hypertension and stroke complications related to preeclampsia (Ahmed et al., 2013; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021; Giorgione et al., 2020). In other words, many researchers suggest that it is important to have some level of continued postpartum care for a year to several years after delivery.

In one case study a woman 10-weeks postpartum was visited by her general nurse practitioner in her home (Ahmed et al., 2013). The nurse practitioner found the patient was throwing up, reported a headache on the left side of her head, and had an altered mental status (Ahmed et al., 2013). After the patient received an MRI, it was found that she had had a postpartum stroke from an cerebral infarction in her left thalamus (Ahmed et al., 2013). Ahmed et al (2013) suggests based on this case study, that routine visits are necessary for the health of new mothers for longer than 60 days after delivery. If this new mother had not received routine postpartum care at this time, she may have experienced more permanent damage or even death (Ahmed et al., 2013).

Policy Recommendations

It is recommended that postpartum Medicaid coverage be extended to one year and include coverage for routine visits to licensed healthcare and mental health professionals.

Data from the American Medical Association in 2019 shows that the largest percentage of healthcare cost in one division of healthcare is hospitalization (American Medical Association, 2019). If postpartum care is available longer and more consistently to recipients of Medicaid, then there is a greater chance that more patients will receive this preventative care, and large costly incidents such as permanent type-2 diabetes and postpartum strokes may be prevented. This would essentially decrease the amount of money Medicaid is spending on hospitalization which costs a lot more than preventative care.

One Utah waiver proposal by Raymond Ward (2021) was presented in the 2021 General Session in an attempt to “provide Medicaid coverage to a postpartum individual whose household income is at or below 200% of the federal poverty level for a period of one year after the individual’s pregnancy” (Ward, 2021, pp. 16–18). Ward (2021) basically presents the idea that if postpartum care is available to more recipients of Medicaid, that more patients will receive this preventative care, and large costly incidents such as permanent type-2 diabetes and postpartum strokes may be prevented. This would essentially decrease the amount of money Medicaid is spending on hospitalizations which cost a lot more than preventative care. He also alludes to the fact that Utah’s suicidal rates are very high, and that we should do everything we can to provide better mental health services to new mothers sense they are at higher risk for depression (Utah Department of Health, 2021; Ward, 2021).

Utah would not be the first state to extend postpartum coverage to one year. As of March 31, 2022, thirty-one states are either implementing, legislating, planning to implement, or have a proposed/pending waiver for similar changes (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021). Murray (2021) and LeBlanc (2021) support the Utah Medicaid adjustment in their articles by explaining that the Biden Administration has approved for no one to be removed from Medicaid until next year. In other words there is a variety of literature justifying the change by bringing up the idea that other states and temporarily the federal government are implementing these changes suggesting that it is a feasible adjustment.

Overall there has been a wide range of research supporting a change in Medicaid postpartum coverage in Utah. Supporting researchers argue that extending postpartum coverage would be more cost effective over an extended period and would improve the health conditions of new mothers. With the recent increase in postpartum related deaths and the steady rise of risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and depression it is critical to enact changes that will provide for accessible postpartum care. Nothing is more important than the health and welfare of our citizens and this request to reform Medicaid coverage is an opportunity to benefit the citizens of the state of Utah medically, mentally, and economically.