Tutoring Centers have been part of college and university campuses for decades, and with good reason. There is little debate that tutoring helps improve learning, retention of ideas, and student grades. There is debate, however, about who should attend tutoring. Tutoring centers often face stigma from students and faculty. The general perception from students is that tutoring is only for low-performing peers: those among them who require developmental support to catch up with peers who perform at a satisfactory level. Faculty perception is often the same; they refer their worst performing students in hopes that a tutor can bring the students up-to-speed. However, both of these groups seem to ignore data that suggests tutoring is beneficial for students at all levels (Cooper, 2010). Perhaps the bigger issue is that if most students feel that tutoring is only for struggling students, and most students do not feel they fall into that category (Cherry, 2019), how do faculty persuade students to attend tutoring sessions?

For years, higher education relied on anecdotal evidence, and the word “mandatory” became taboo. A quick search of comments after an article arguing for mandatory tutoring reveals the following:

Mandatory? I’ve worked in academic services for 25 years, and there is one thing I really HATE, and that is mandatory anything. As it was once put to me, mandatory tutoring is like teaching a pig to sing. All you do is waste your time and annoy the pig. (no insult to students intended) But this is NOT a magic solution…We have a developmental math SI here. Two years ago, it was made mandatory. Believe me, it wasn’t my idea. While we doubled attendance, the grade distribution for the students attending all the time, and those going just a few times showed the same grade distribution as it had before it was mandatory. In our case, it means, even though they are coming to what is a great academic support, their grade performance also depends on things like doing homework, and studying for tests. How do you fix that? Mandatory study hall? (Sara G., as cited in Fain, 2012, paras. 28–33)

Many others tell stories illustrating that mandatory tutoring does not work. The data, however, tells a different story. Author J. Wells (2016) reports that recent studies show beneficial results from mandatory tutoring, while very few studies show a lack of benefit (Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Bell & Stutts, 1997; Clark, 1985). Still, many administrators hesitate to mandate anything.

What is trending with administrators currently are high impact practices. These areas include first-year experience, supplemental instruction, freshman orientation, tutoring, and student success courses (Center for Community College Student Engagement, 2012). Most of these practices feature data showing significant improvement for those using the programs, but the problem lies with the few number of students who take advantage of these resources. K. McClenney says that about 75 percent of college students report that they had to take academic placement tests to determine the need for developmental placement, yet only 28 percent of students studied for these tests. She further explains that 48 percent of community colleges offer study aids for these placement tests and only 13 percent make test preparation mandatory. These numbers, she argues, strongly suggest that many community college students could test out of developmental courses with study aids and mandatory preparation, accelerating their paths to degrees (as cited in Fain, 2012).

When we planned our mandatory tutoring study to quantify the benefits of writing center tutoring for students, we faced several obstacles. The first obstacle was the English Department chair. He was concerned with upset students, over-worked peer tutors, and the writing center’s ability to accommodate one to two hundred additional appointments. After reading literature on the benefits of mandatory tutoring, however, he consented. The second obstacle was faculty. While some were enthusiastic about the study, others questioned if the tutoring would be beneficial to students forced to attend. Ultimately, we found five professors willing to participate with their English 1010, Introduction to Writing classes. The final obstacle was the students themselves. We set an incentive of ten percent of an essay’s grade (added as a separate grading item) to motivate students to attend, but we wanted them to have a good attitude also to insure productive sessions. To mitigate negativity, our Director of Learning Resources presented to each class and talked about the study. His goal, primarily, was to refute the stigma that tutoring is for low-performing students.

In order to have qualitative as well as quantitative data, we created two student perception surveys. Our director administered the first before tutoring, and the second after the class had completed all mandatory tutoring sessions. Of 165 students in the study, 111 students (73%) had never visited the writing center prior to the study. Of those, only 73% completed at least one tutoring session (minimum requirement). Here is the Likert scale used in the survey:

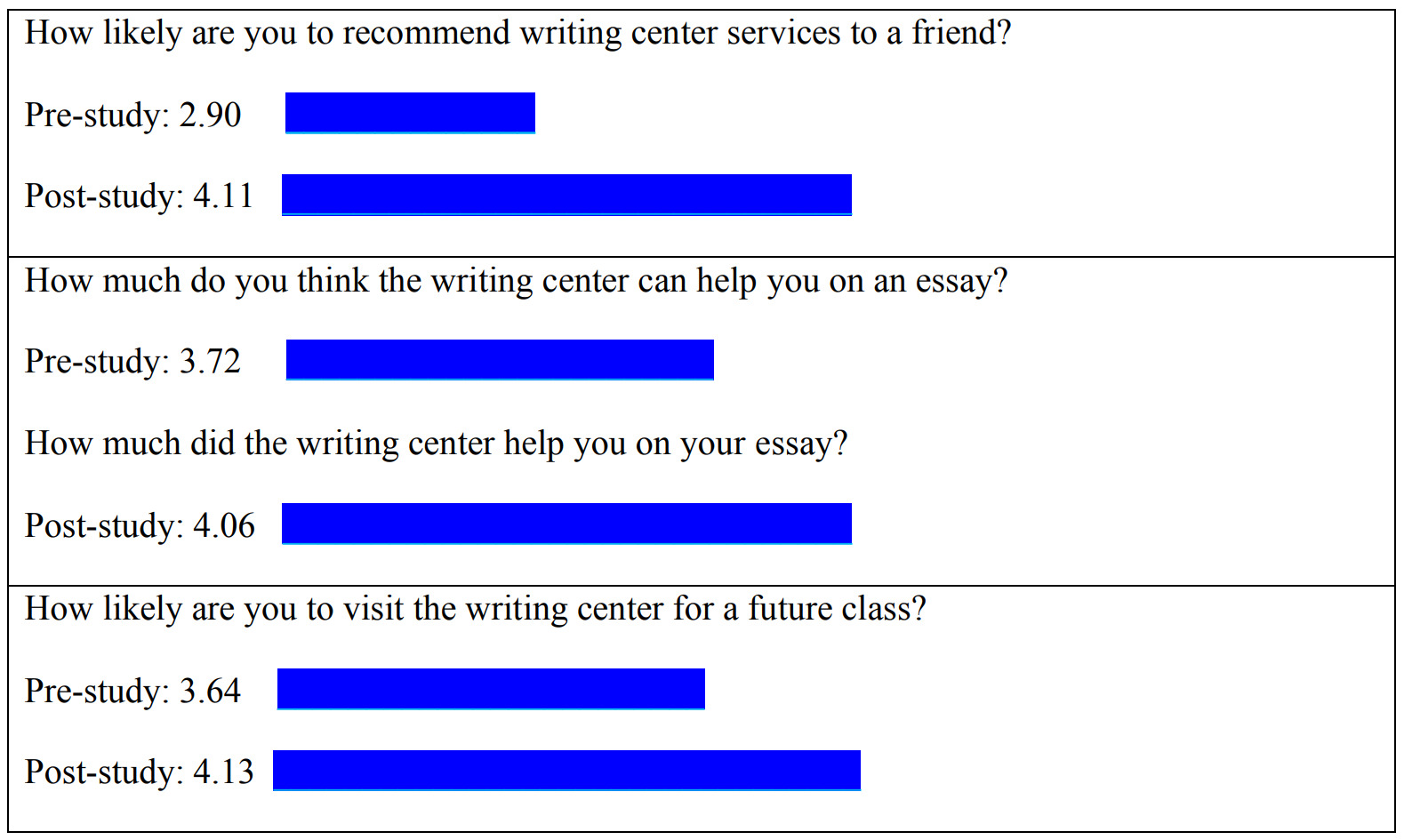

The following are the survey questions and the results from those who had not visited previously but attended the mandatory tutoring sessions:

In all categories, attending mandatory tutoring raised student perception of the writing center by a substantial amount, correcting the stigma among those participating in the study that tutoring is only for other, lower-performing students.

Methodology

In spring 2019, the Writing Center obtained essay scores and course grades from five instructors and twelve sections of English 1010 and English 1010D at the university for 111 new freshmen. Administrators excluded students from the study who did not submit an essay. In eight sections, it was mandatory for students to attend the writing center for assistance on at least one essay. Administrators asked instructors to incentivize visits at a weight of ten percent of the essay’s score. For the analysis, the ten percent was not part of the predicted essay score. Instructors added the score as a separate line item in their gradebooks. For the overall grade, ten percent on one essay would have very little impact on a student’s total grade, less than three percent on the overall 100 percent. The remaining four sections were control courses, and administrators asked instructors to promote the writing center in the same manner they normally would in their composition courses.

Results

Outcomes were quite different for new freshmen who utilize the writing center compared to those who did not take advantage of the services. The average grade on the essay for those who used the center was 2.94 compared to 1.60 for those who did not, roughly a B compared to failing grades, below a C- on average. The average grade in the course for those who used the center was 3.25 compared to 2.18 for other new freshmen who did not use the writing center.

New freshmen who took their papers to the writing center had a higher ACT Composite Score (19) and high school GPA (3.33) than students not taking advantage of services (18 and 3.02). The index score (high school GPA X 10 + ACT Composite) was 48 and 52 respectively, higher for those following their instructor’s guidelines.

One could argue that the difference was due solely to the lack of preparation in high school of those who did not attend tutoring. To counter this argument, the researchers used a binary logistic regression to predict grades on the essay and grades in the English courses. This was chosen because grades were bimodal; therefore, the outcomes were changed to earning a B or higher and C or higher on the essay and for the course grade.

In order to control for differences in high school preparation, the researchers used covariates or control variables in the analyses. Results were similar using different covariates (high school GPA, ACT score or index score). Therefore, researchers chose the ACT score because of the larger sample size with this data.

Discussion

When controlling for students’ ACT Composite scores, student compliance with taking their paper to the writing center was positively associated with earning a B or higher and earning a C or higher on their essay. The same was true for their course grade (all tests statistically significant). Therefore, new freshmen are making a wise choice to utilize tutoring services on campus. Interestingly, of the students in the four control classes where attending the writing center was not mandated but promoted as each instructor normally would, no students attended the writing center during the semester. Therefore, it seems that instructors are making a good choice to encourage tutoring by requiring use of the writing center as part of their courses. In addition, administrators would do well to use data in place of anecdotal evidence when considering mandatory tutoring.

Authors’ Note

Special thanks for editing and formatting advice from Brittany Bennett, Writing Center coordinator, Dixie State University.

While Brittany Bennett works with tutors and students in the Writing Center and Rob Gray oversees Writing Center operations, neither gathered nor analyzed data from the study. Jeffery Hoyt, who works in a division outside of Academic Affairs and Learning Services, calculated results. Thus, no conflict of interest exists from any participants in this study.